Bulletproof Type Safety in Gleam: From Database to Client

Building end-to-end type-safe applications with Gleam, PostgreSQL, and shared domain models for instant feedback and zero runtime surprises.

Let’s learn how to build end-to-end, type-safe applications with Gleam.

We’ll use a PostgreSQL database to store our data and Gleam for both the frontend and backend.

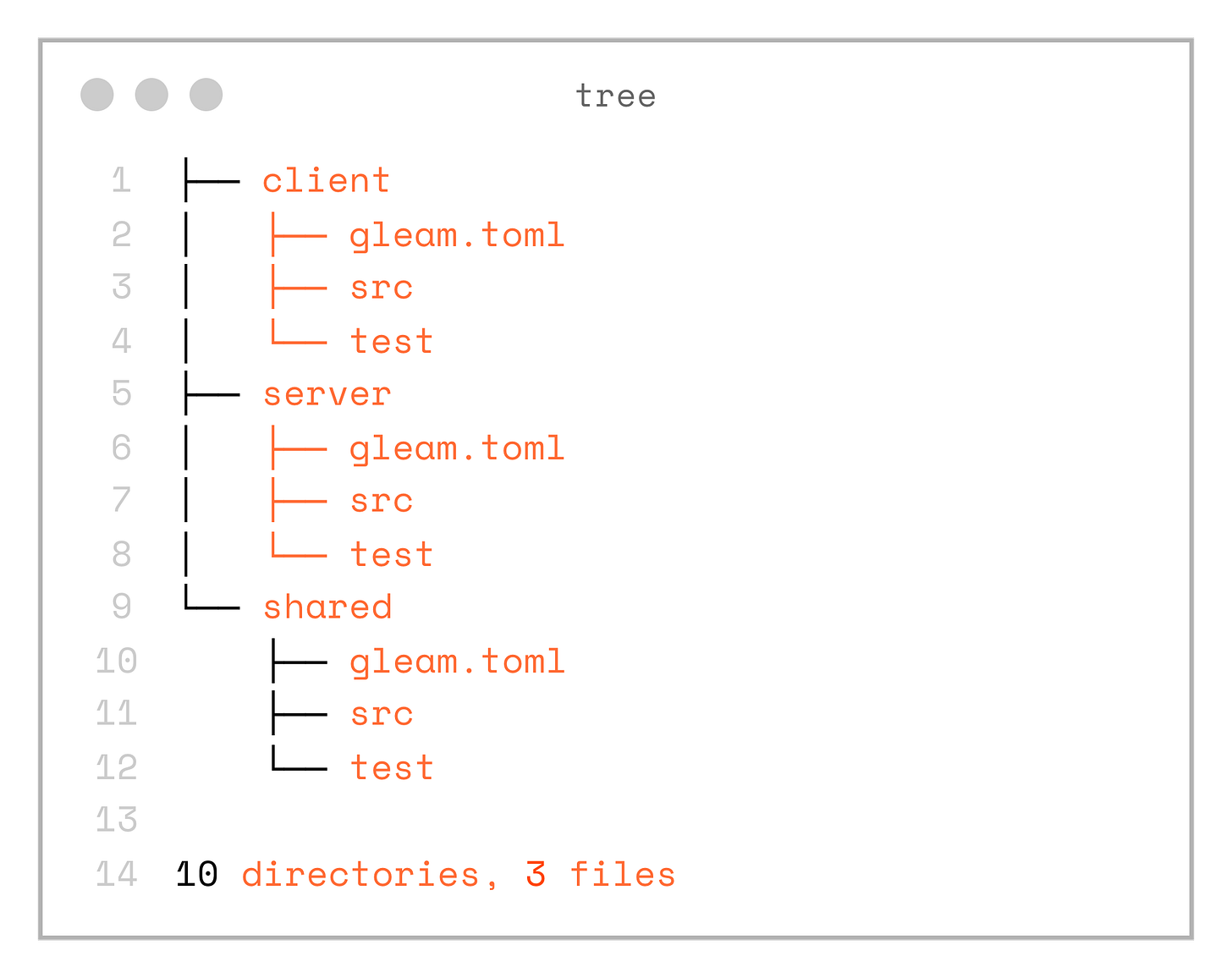

Project structure

First, let’s setup the project structure. We will need 3 top level folders: server, client and shared. Each of them is a Gleam project:

gleam new shared

gleam new client

gleam new serverSo as the result we will get this folder structure:

.

├── client

│ ├── gleam.toml

│ ├── src

│ └── test

├── server

│ ├── gleam.toml

│ ├── src

│ └── test

└── shared

├── gleam.toml

├── src

└── test

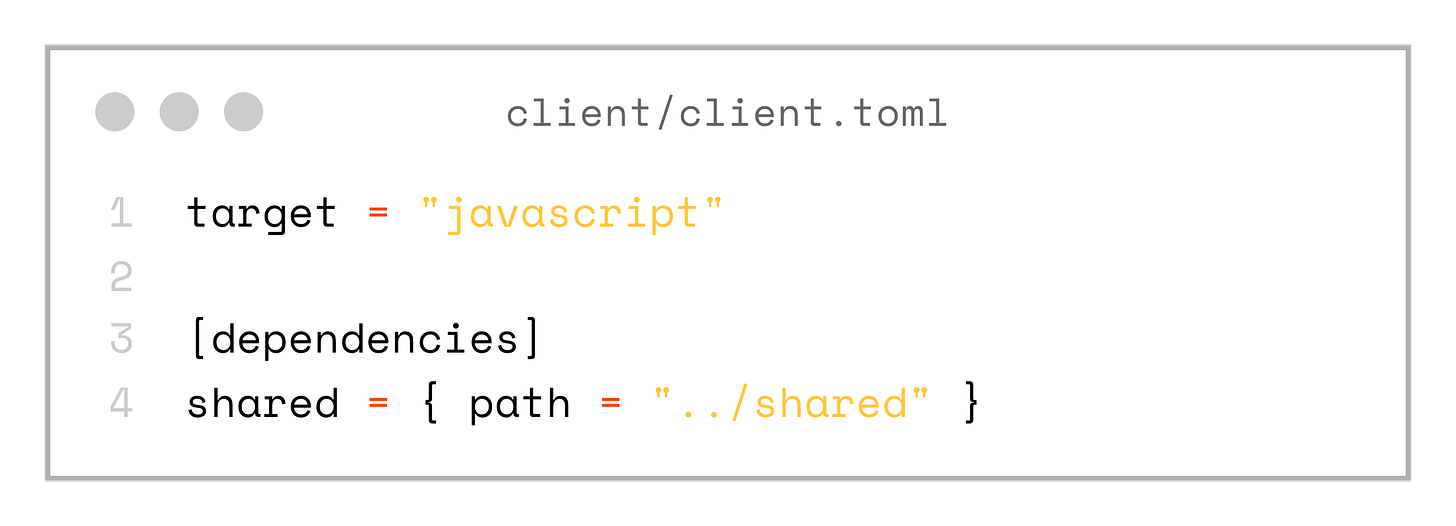

10 directories, 3 filesNote, that both client and server are using local dependency on the shared project. Aslo client is configured with javascript as the target.

target = "javascript"

[dependencies]

shared = { path = "../shared" }Preparing Postgres Database

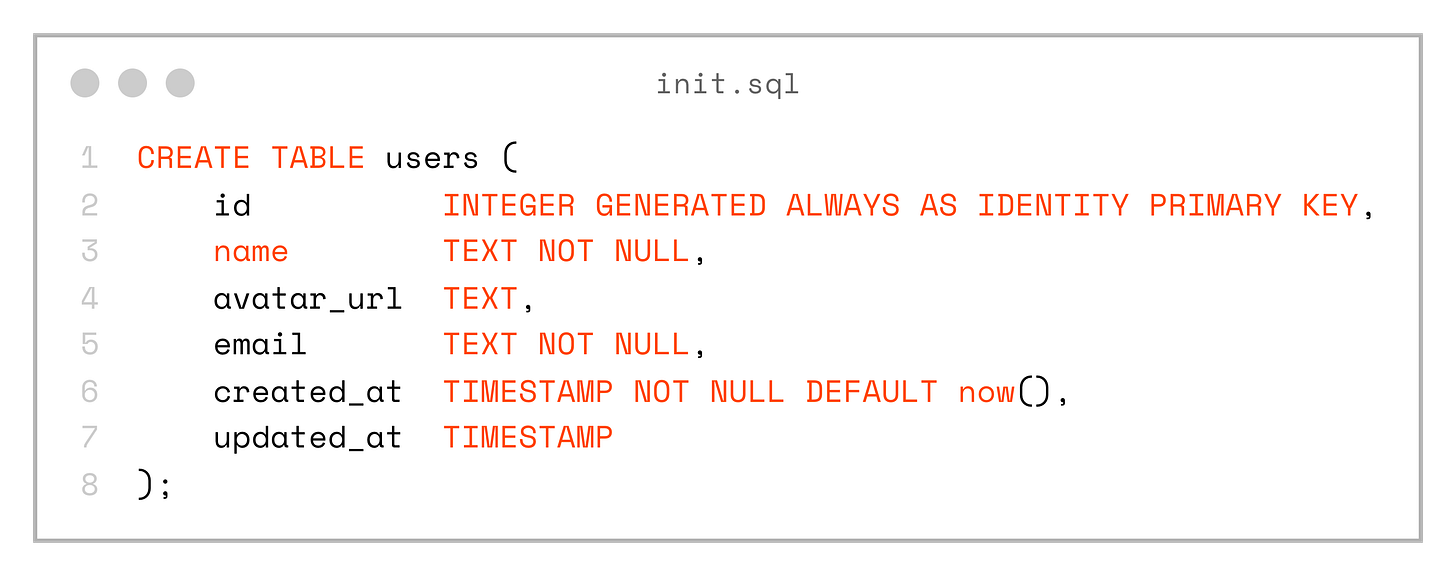

Let’s apply a pragmatic Domain-Driven Design (DDD) approach. Suppose we want to store and manage User entities. A sensible first step is to design the database schema, starting with a simple users table that contains a few core fields.

CREATE TABLE users (

id INTEGER GENERATED ALWAYS AS IDENTITY PRIMARY KEY,

name TEXT NOT NULL,

avatar_url TEXT,

email TEXT NOT NULL,

created_at TIMESTAMP NOT NULL DEFAULT now(),

updated_at TIMESTAMP

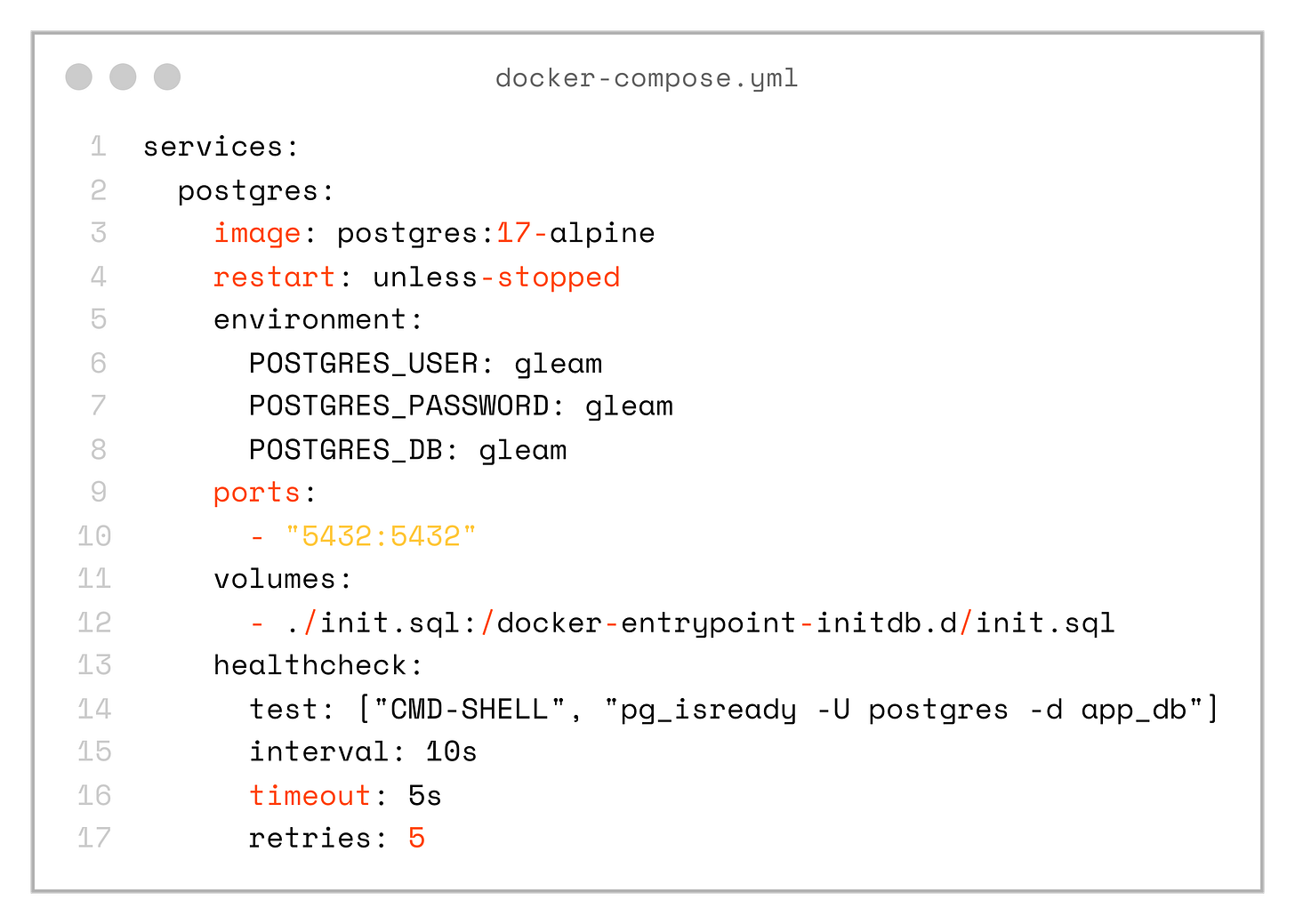

);Next, let’s spin up a local database in a Docker container so we can use it for further development.

services:

postgres:

image: postgres:17-alpine

restart: unless-stopped

environment:

POSTGRES_USER: gleam

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: gleam

POSTGRES_DB: gleam

ports:

- "5432:5432"

volumes:

- ./init.sql:/docker-entrypoint-initdb.d/init.sql

healthcheck:

test: ["CMD-SHELL", "pg_isready -U postgres -d app_db"]

interval: 10s

timeout: 5s

retries: 5Gleam SQL queries

How do we bring knowledge of the database schema into our Gleam code?

We don’t need a complex ORM or any magical framework. Instead, we can rely on plain SQL combined with a small amount of code generation.

To do this, let’s install the excellent squirrel library:

gleam add --dev squirrelNotice the --dev flag — this isn’t even a runtime dependency.

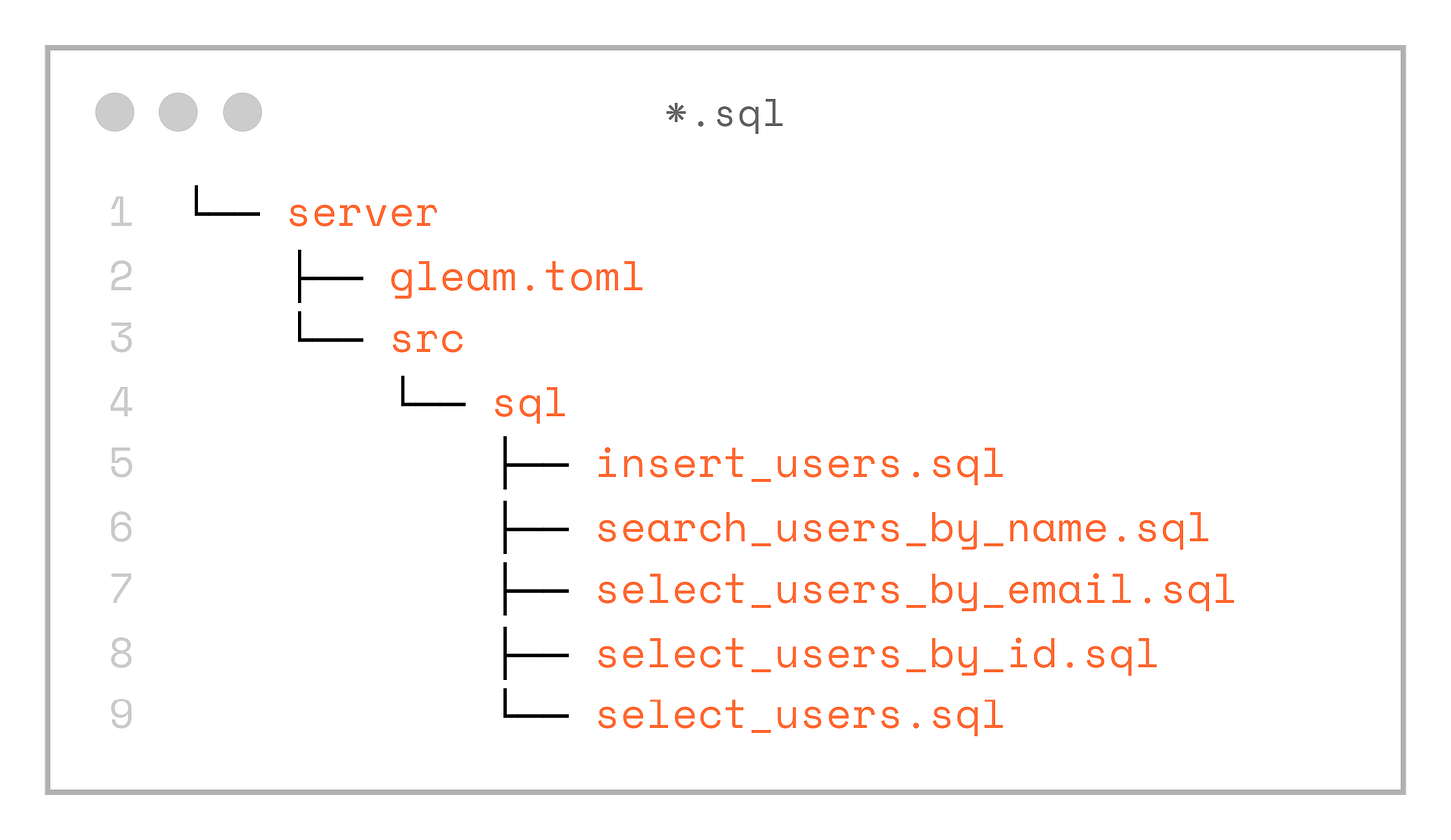

Next, let’s add queries, written as plain SQL, to the server/src/sql directory.

└── server

├── gleam.toml

└── src

└── sql

├── insert_users.sql

├── search_users_by_name.sql

├── select_users_by_email.sql

├── select_users_by_id.sql

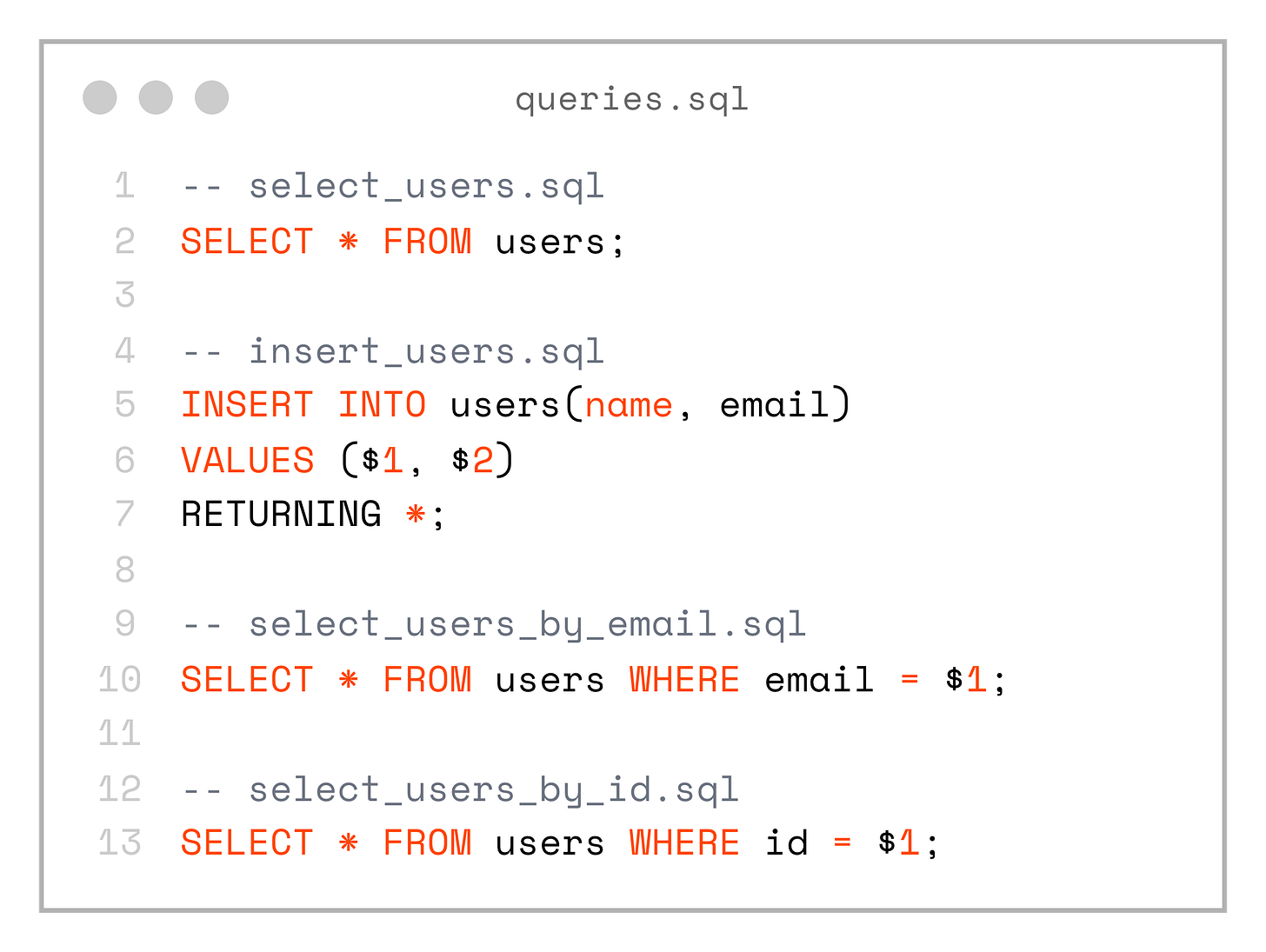

└── select_users.sqlSo we end up with the following SQL files: select_users.sql, select_users_by_id.sql, select_users_by_email.sql, insert_users.sql

-- select_users.sql

SELECT * FROM users;

-- insert_users.sql

INSERT INTO users(name, email)

VALUES ($1, $2)

RETURNING *;

-- select_users_by_email.sql

SELECT * FROM users WHERE email = $1;

-- select_users_by_id.sql

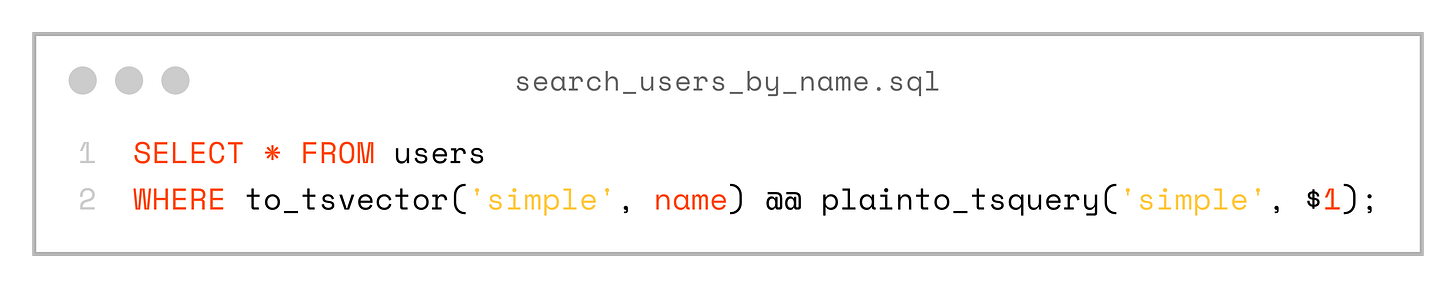

SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = $1;These queries are trivial for now, but we’re not limited in any way — each SQL file can contain any SQL that PostgreSQL understands. For example, we can start using full-text search right away:

SELECT * FROM users

WHERE to_tsvector('simple', name) @@ plainto_tsquery('simple', $1);The SQL file names can be anything — it’s up to you to choose a convention. Keep in mind, however, that the generated code will use the file name both for the Gleam function name and for the generated record types.

I currently follow this pattern: the operation (e.g. select, insert, update, delete), followed by the table name, and then an optional condition.

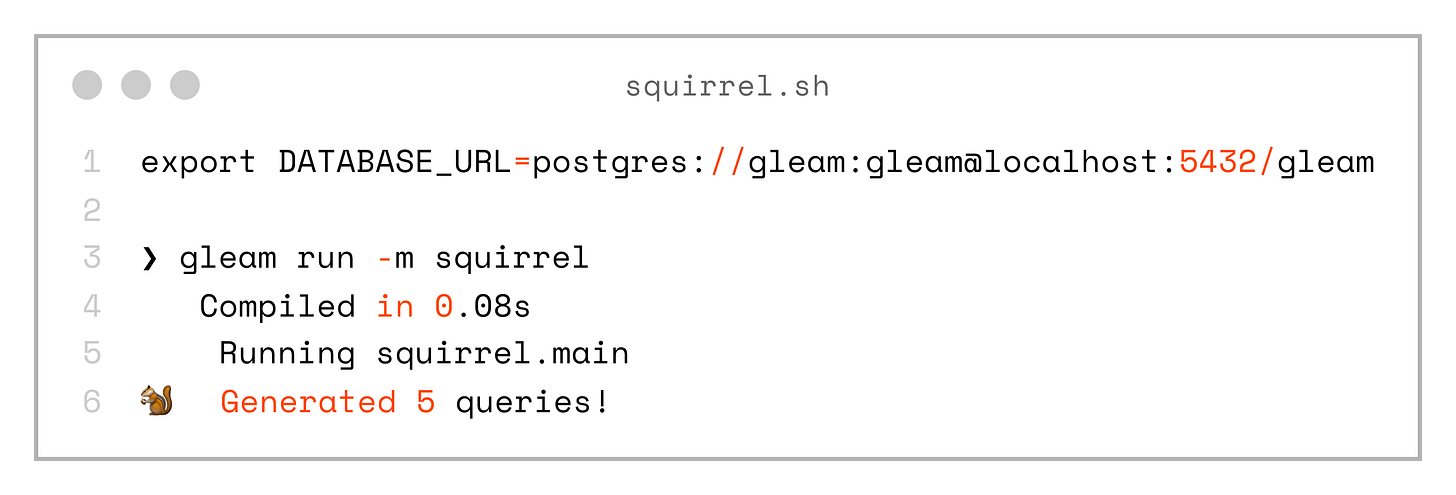

Before we can use squirrel for code generation, we need to set the DATABASE_URL environment variable.

export DATABASE_URL=postgres://gleam:gleam@localhost:5432/gleam

❯ gleam run -m squirrel

Compiled in 0.08s

Running squirrel.main

🐿️ Generated 5 queries!The squirrel library detected SQL files and generated 5 queries, that looks promising! Now that we have the server/src/sql.gleam file, let’s take a look at what was generated.

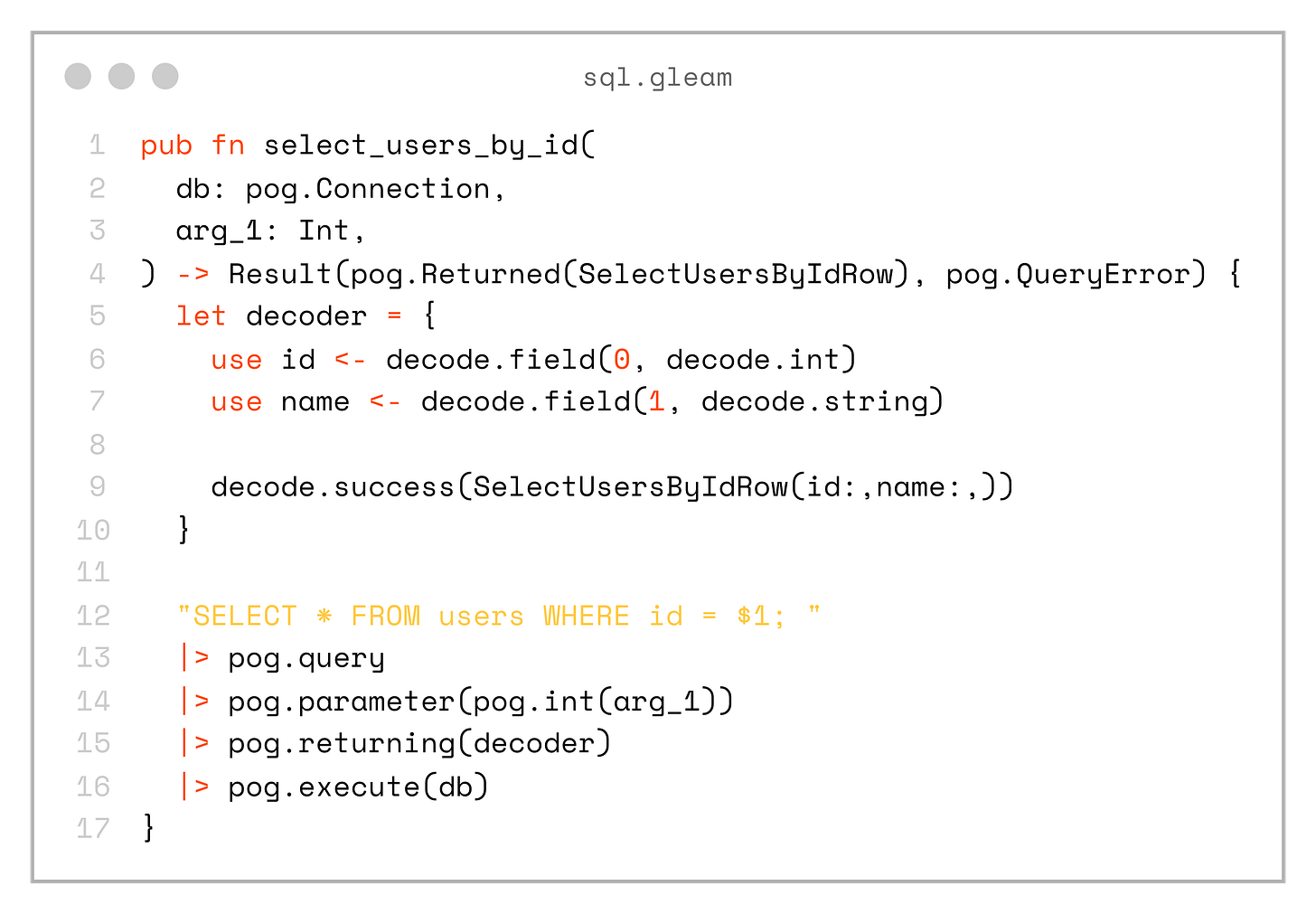

For example, here is the select_user_by_id function (most of the decoding logic is omitted for simplicity):

pub fn select_users_by_id(

db: pog.Connection,

arg_1: Int,

) -> Result(pog.Returned(SelectUsersByIdRow), pog.QueryError) {

let decoder = {

use id <- decode.field(0, decode.int)

use name <- decode.field(1, decode.string)

decode.success(SelectUsersByIdRow(id:,name:,))

}

"SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = $1; "

|> pog.query

|> pog.parameter(pog.int(arg_1))

|> pog.returning(decoder)

|> pog.execute(db)

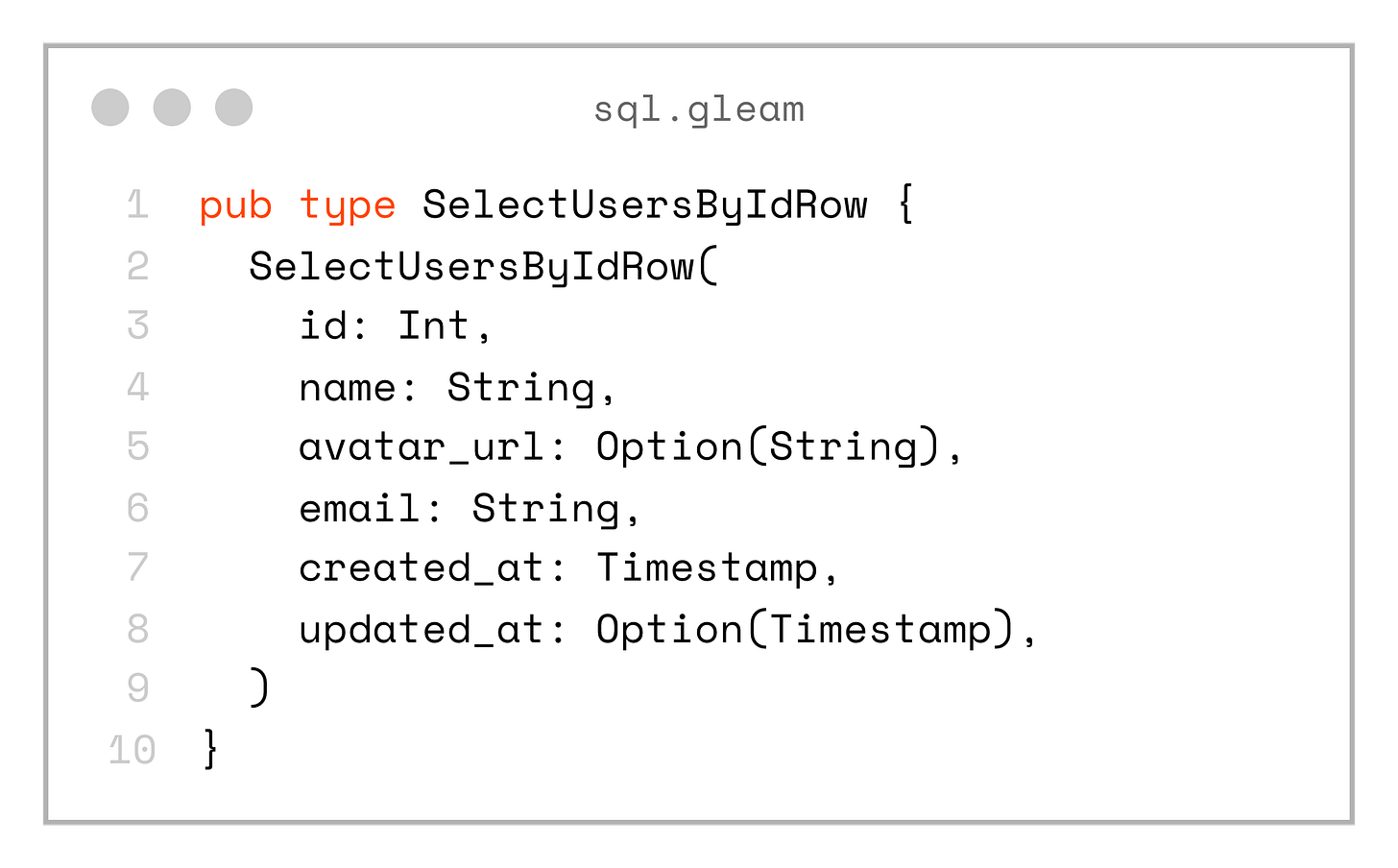

}And also the custom record type SelectUsersByIdRow:

pub type SelectUsersByIdRow {

SelectUsersByIdRow(

id: Int,

name: String,

avatar_url: Option(String),

email: String,

created_at: Timestamp,

updated_at: Option(Timestamp),

)

}The same code is generated for the other queries as well.

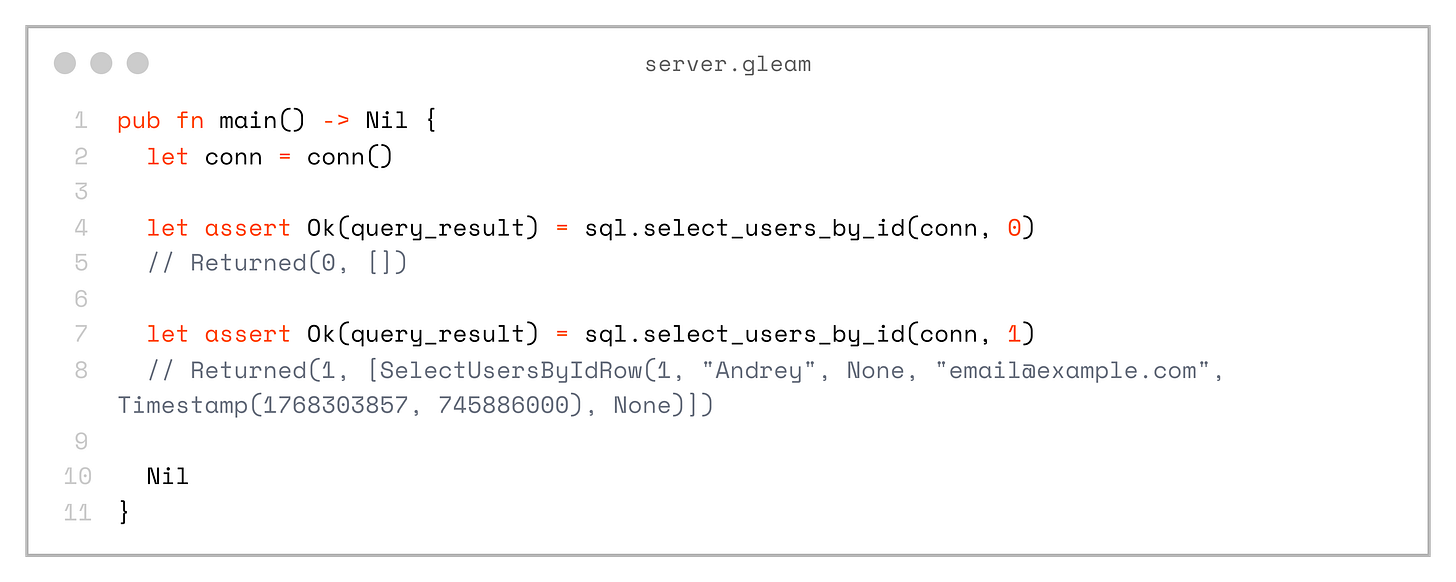

Next, let’s see how we can execute these queries from the main function of our application:

pub fn main() -> Nil {

let conn = conn()

let assert Ok(query_result) = sql.insert_users(conn, "Andrey", "email@example.com")

let assert Ok(inserted_user) = list.first(query_result.rows)

// InsertUsersRow(2, "Andrey", None, "email@example.com", Timestamp(1768325274, 201229000), None)

}And also query by id:

pub fn main() -> Nil {

let conn = conn()

let assert Ok(query_result) = sql.select_users_by_id(conn, 0)

// Returned(0, [])

let assert Ok(query_result) = sql.select_users_by_id(conn, 1)

// Returned(1, [SelectUsersByIdRow(1, "Andrey", None, "email@example.com", Timestamp(1768303857, 745886000), None)])

Nil

}This is already really handy — and pretty cool! It’s also type-safe, since the queries and record types were generated based on the actual database schema; the squirrel library performs schema introspection automatically.

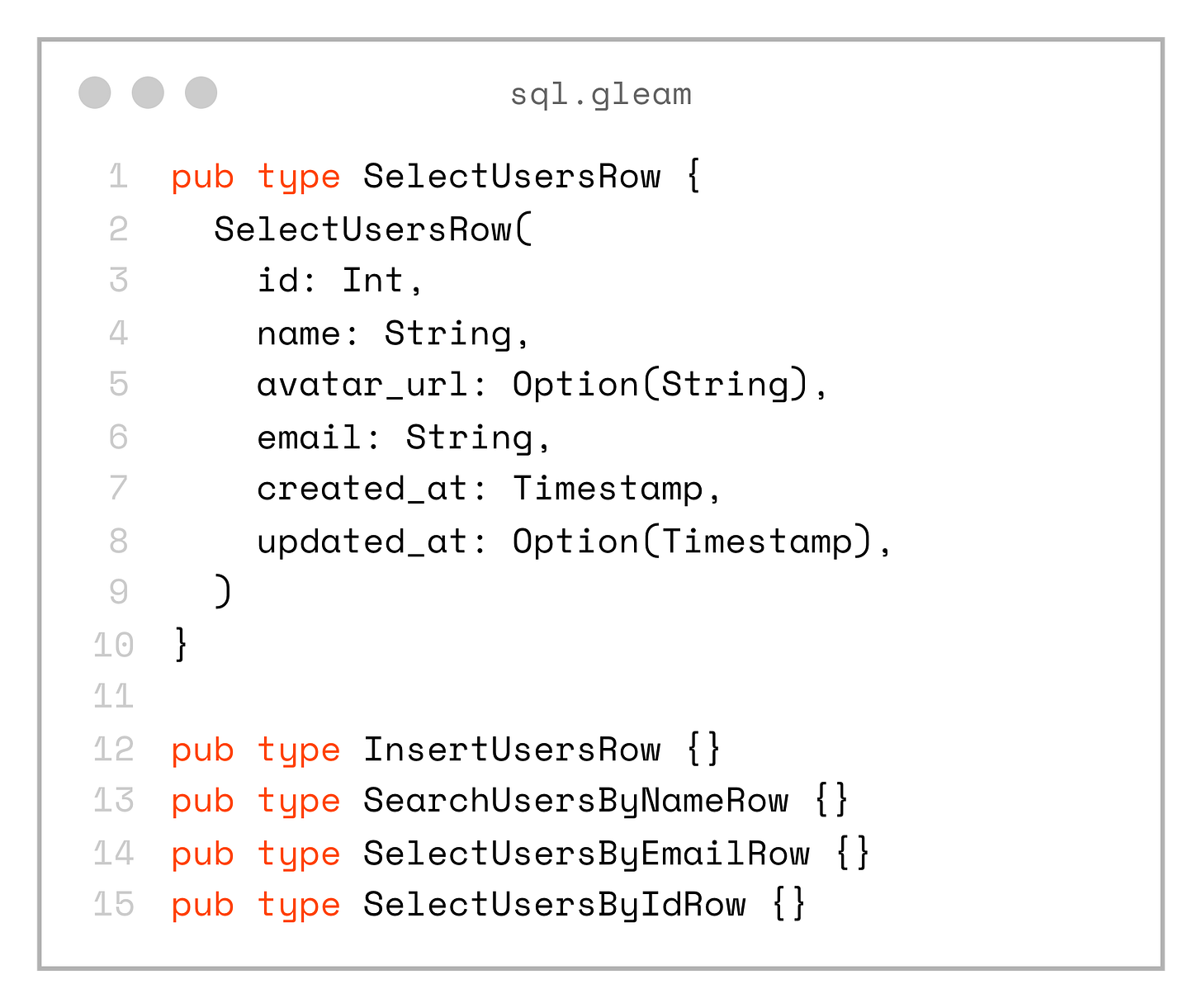

The only downside is that we end up with multiple record types that actually represent the same logical type:

pub type SelectUsersRow {

SelectUsersRow(

id: Int,

name: String,

avatar_url: Option(String),

email: String,

created_at: Timestamp,

updated_at: Option(Timestamp),

)

}

pub type InsertUsersRow {}

pub type SearchUsersByNameRow {}

pub type SelectUsersByEmailRow {}

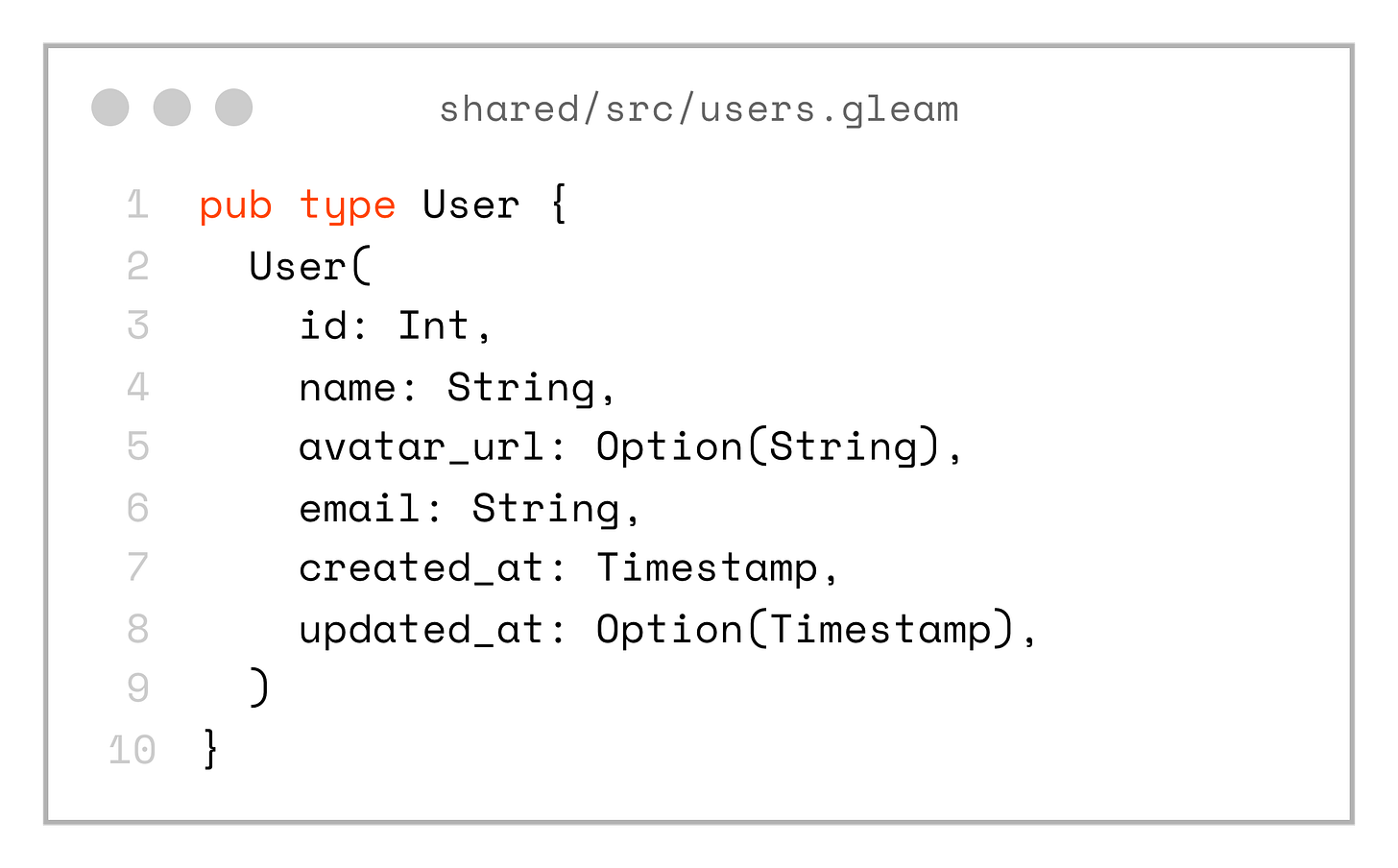

pub type SelectUsersByIdRow {}The solution to that is to create a domain model in the shared project:

pub type User {

User(

id: Int,

name: String,

avatar_url: Option(String),

email: String,

created_at: Timestamp,

updated_at: Option(Timestamp),

)

}Now we can create a set of mappers to convert the SQL-generated types into our domain types:

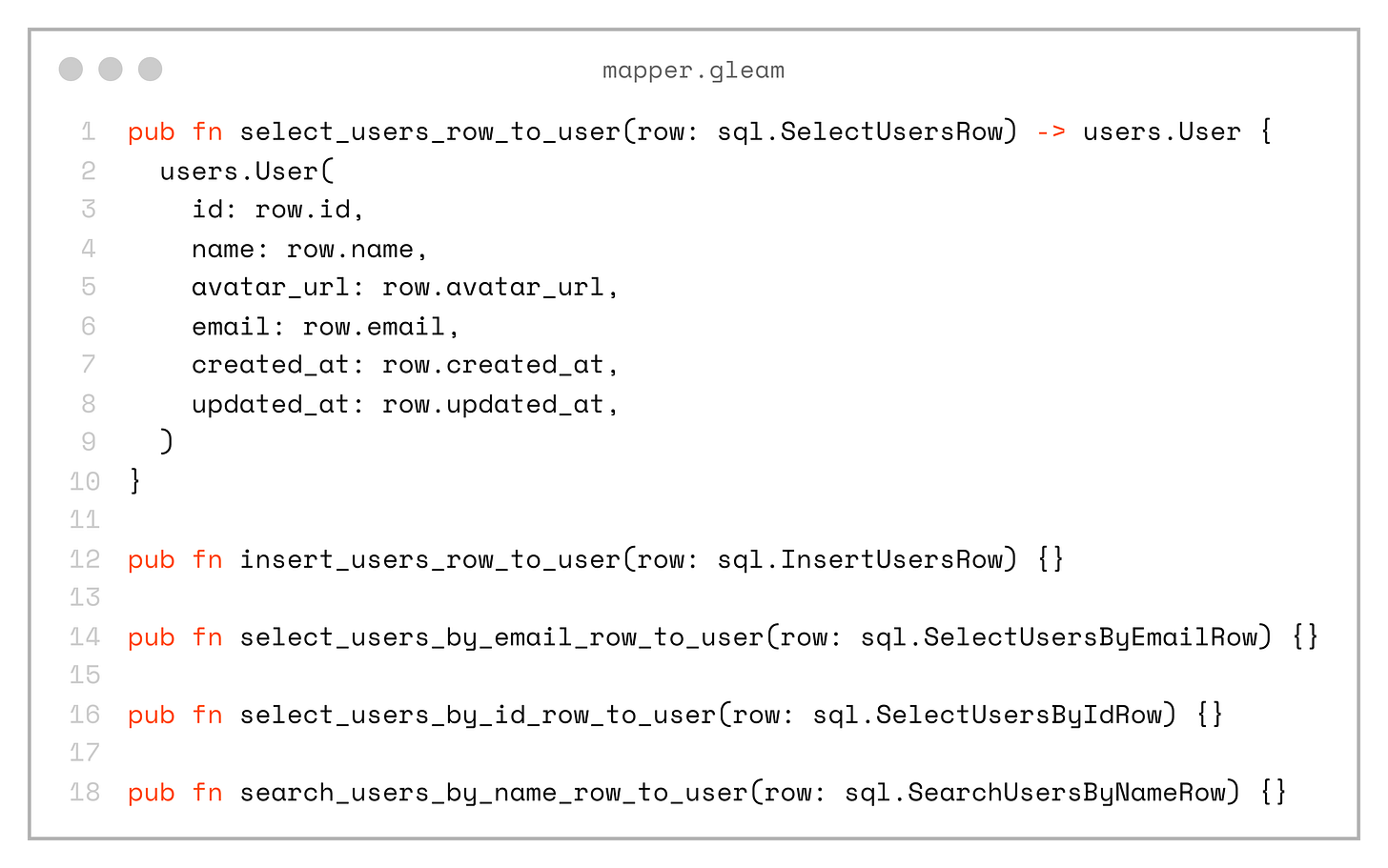

pub fn select_users_row_to_user(row: sql.SelectUsersRow) -> users.User {

users.User(

id: row.id,

name: row.name,

avatar_url: row.avatar_url,

email: row.email,

created_at: row.created_at,

updated_at: row.updated_at,

)

}

pub fn insert_users_row_to_user(row: sql.InsertUsersRow) {}

pub fn select_users_by_email_row_to_user(row: sql.SelectUsersByEmailRow) {}

pub fn select_users_by_id_row_to_user(row: sql.SelectUsersByIdRow) {}

pub fn search_users_by_name_row_to_user(row: sql.SearchUsersByNameRow) {}Yes, this approach introduces some code duplication, and when there’s a one-to-one mapping with the domain model it can feel redundant. But, in real-world applications it’s often much more useful, as it adds a layer of abstraction that can hide the underlying database structure, allow remapping of fields, and more.

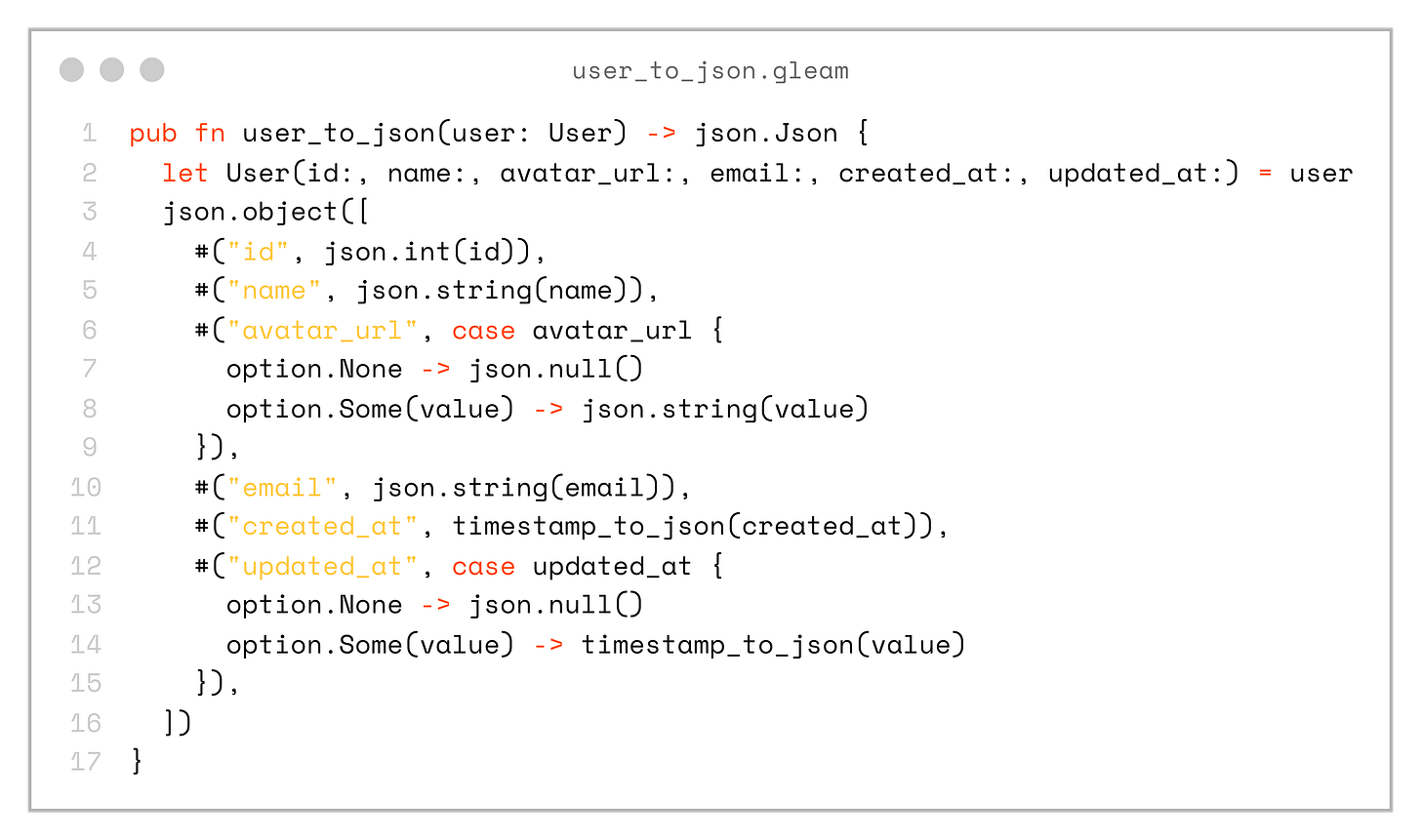

Once we have a shared User type as our domain model, we can use it to send data over the wire — for example, in a JSON REST API.

There are also language server (LSP) commands that can automatically generate _to_json and _from_json functions for us:

pub fn user_to_json(user: User) -> json.Json {

let User(id:, name:, avatar_url:, email:, created_at:, updated_at:) = user

json.object([

#("id", json.int(id)),

#("name", json.string(name)),

#("avatar_url", case avatar_url {

option.None -> json.null()

option.Some(value) -> json.string(value)

}),

#("email", json.string(email)),

#("created_at", timestamp_to_json(created_at)),

#("updated_at", case updated_at {

option.None -> json.null()

option.Some(value) -> timestamp_to_json(value)

}),

])

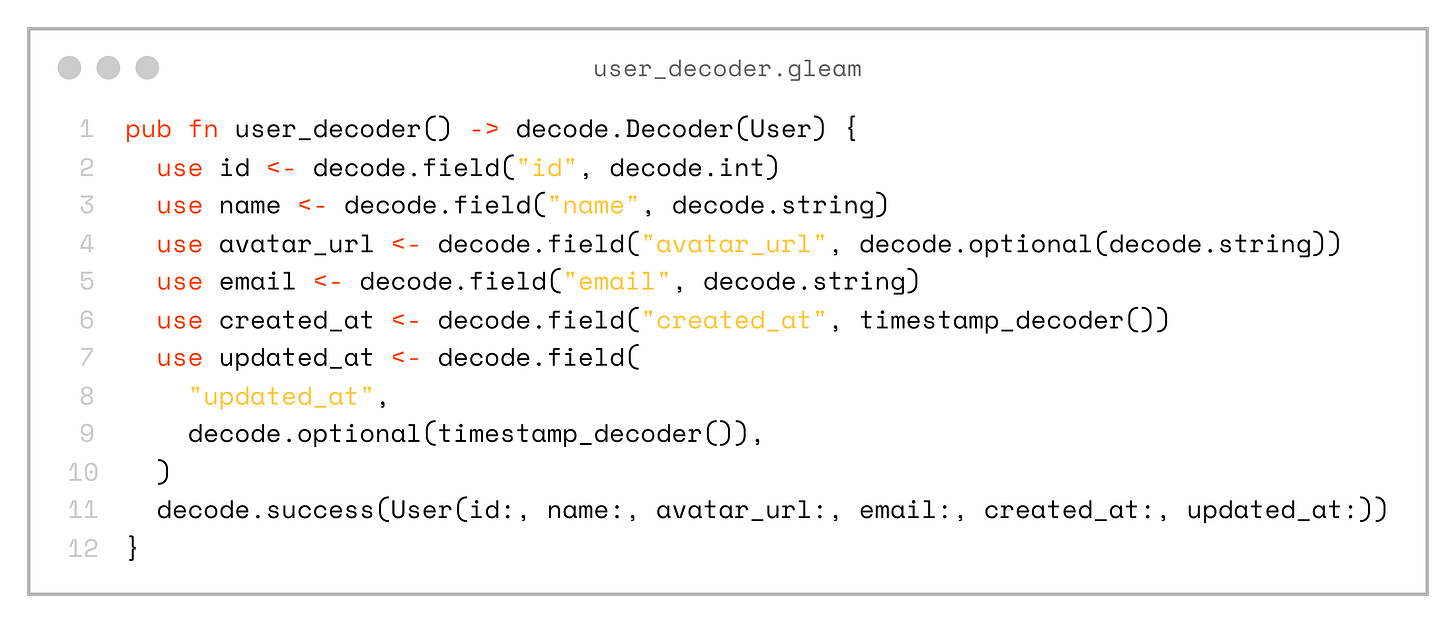

}And a decoder:

pub fn user_decoder() -> decode.Decoder(User) {

use id <- decode.field("id", decode.int)

use name <- decode.field("name", decode.string)

use avatar_url <- decode.field("avatar_url", decode.optional(decode.string))

use email <- decode.field("email", decode.string)

use created_at <- decode.field("created_at", timestamp_decoder())

use updated_at <- decode.field(

"updated_at",

decode.optional(timestamp_decoder()),

)

decode.success(User(id:, name:, avatar_url:, email:, created_at:, updated_at:))

}

Don’t forget that we place this domain type and its encode/decode functions into a shared project. This means both the server and client will work with the same entities, which reduces friction and the possibility of errors.

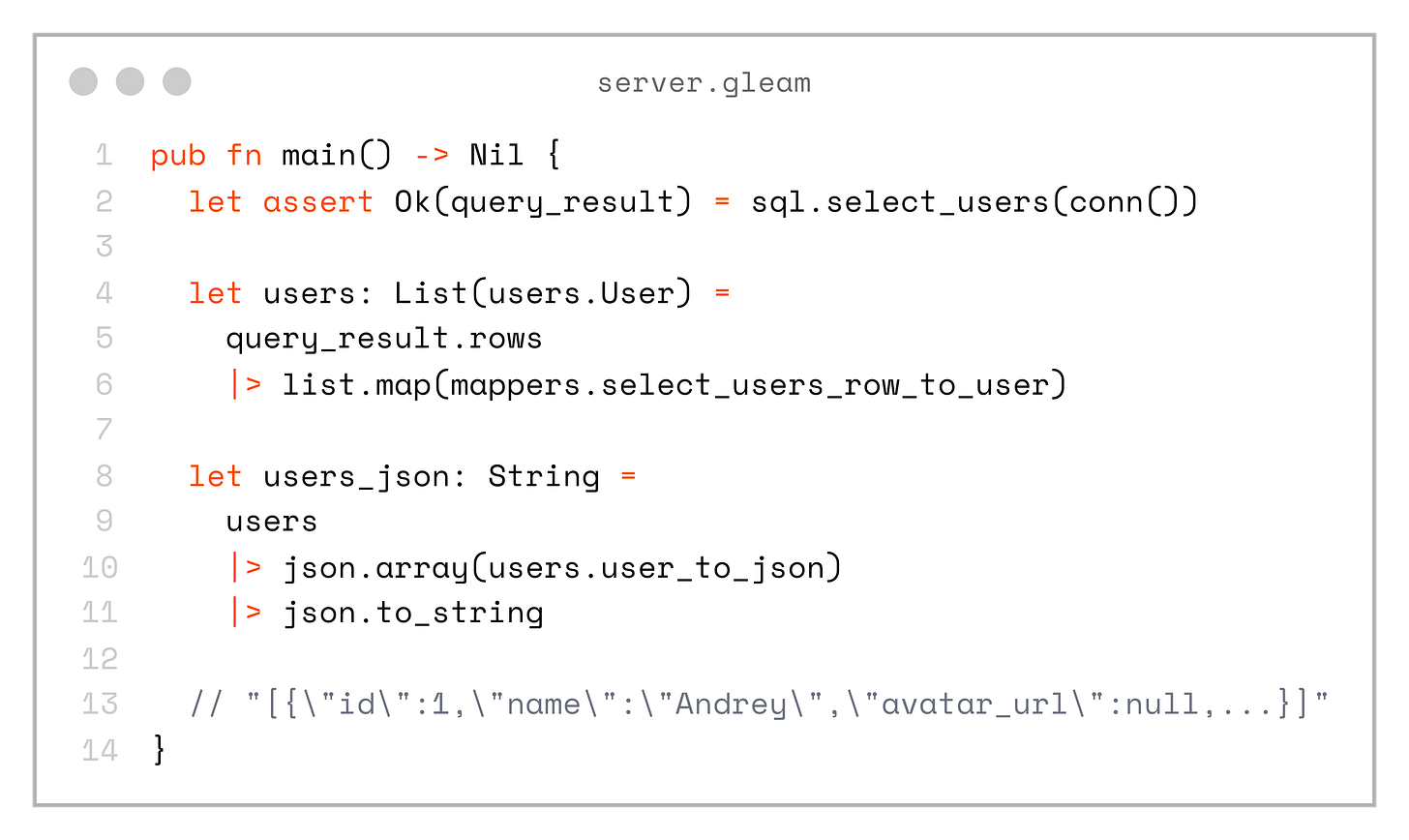

Let’s look at an example from the server, where we fetch users from the database, map them to the domain model type, and encode them to JSON — making them ready to be sent in an API response:

pub fn main() -> Nil {

let assert Ok(query_result) = sql.select_users(conn())

let users: List(users.User) =

query_result.rows

|> list.map(mappers.select_users_row_to_user)

let users_json: String =

users

|> json.array(users.user_to_json)

|> json.to_string

// "[{\"id\":1,\"name\":\"Andrey\",\"avatar_url\":null,...}]"

}Moving to the client side

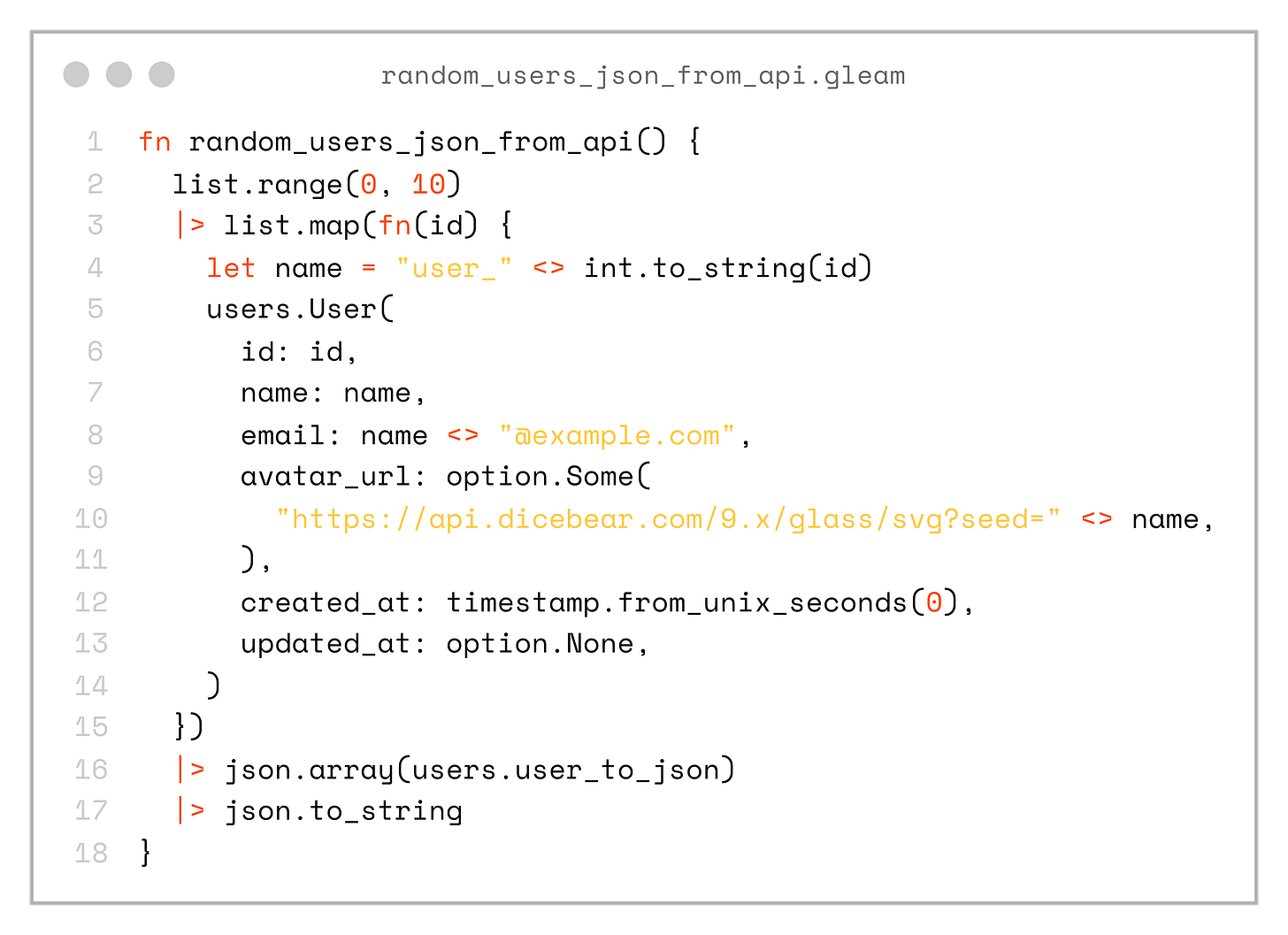

Finally, it’s time to move to the frontend. Here’s a function that simulates the JSON response from our backend:

fn random_users_json_from_api() {

list.range(0, 10)

|> list.map(fn(id) {

let name = "user_" <> int.to_string(id)

users.User(

id: id,

name: name,

email: name <> "@example.com",

avatar_url: option.Some(

"https://api.dicebear.com/9.x/glass/svg?seed=" <> name,

),

created_at: timestamp.from_unix_seconds(0),

updated_at: option.None,

)

})

|> json.array(users.user_to_json)

|> json.to_string

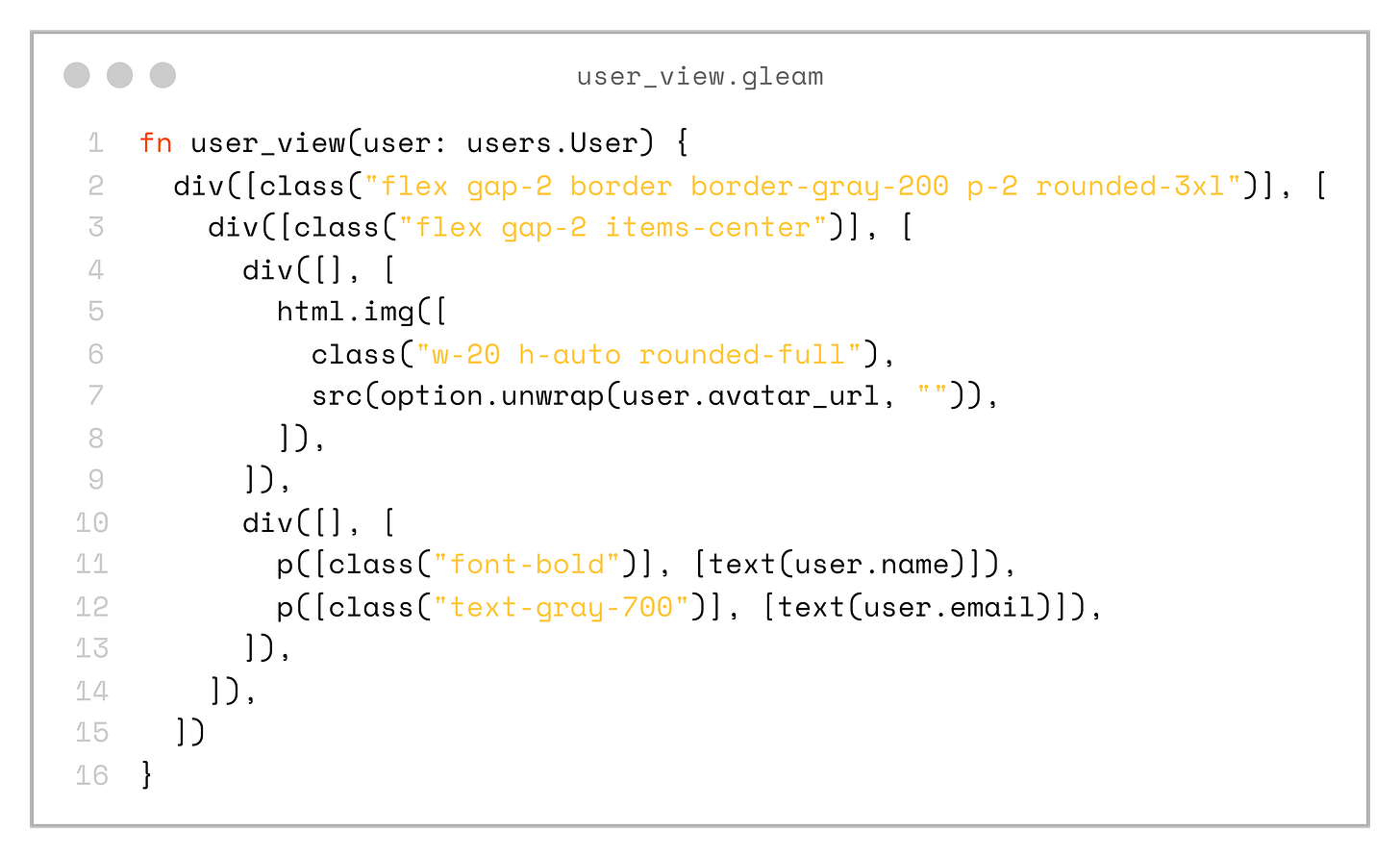

}We can define a user_view helper function in the client app, which specifies how to render our User type:

fn user_view(user: users.User) {

div([class("flex gap-2 border border-gray-200 p-2 rounded-3xl")], [

div([class("flex gap-2 items-center")], [

div([], [

html.img([

class("w-20 h-auto rounded-full"),

src(option.unwrap(user.avatar_url, "")),

]),

]),

div([], [

p([class("font-bold")], [text(user.name)]),

p([class("text-gray-700")], [text(user.email)]),

]),

]),

])

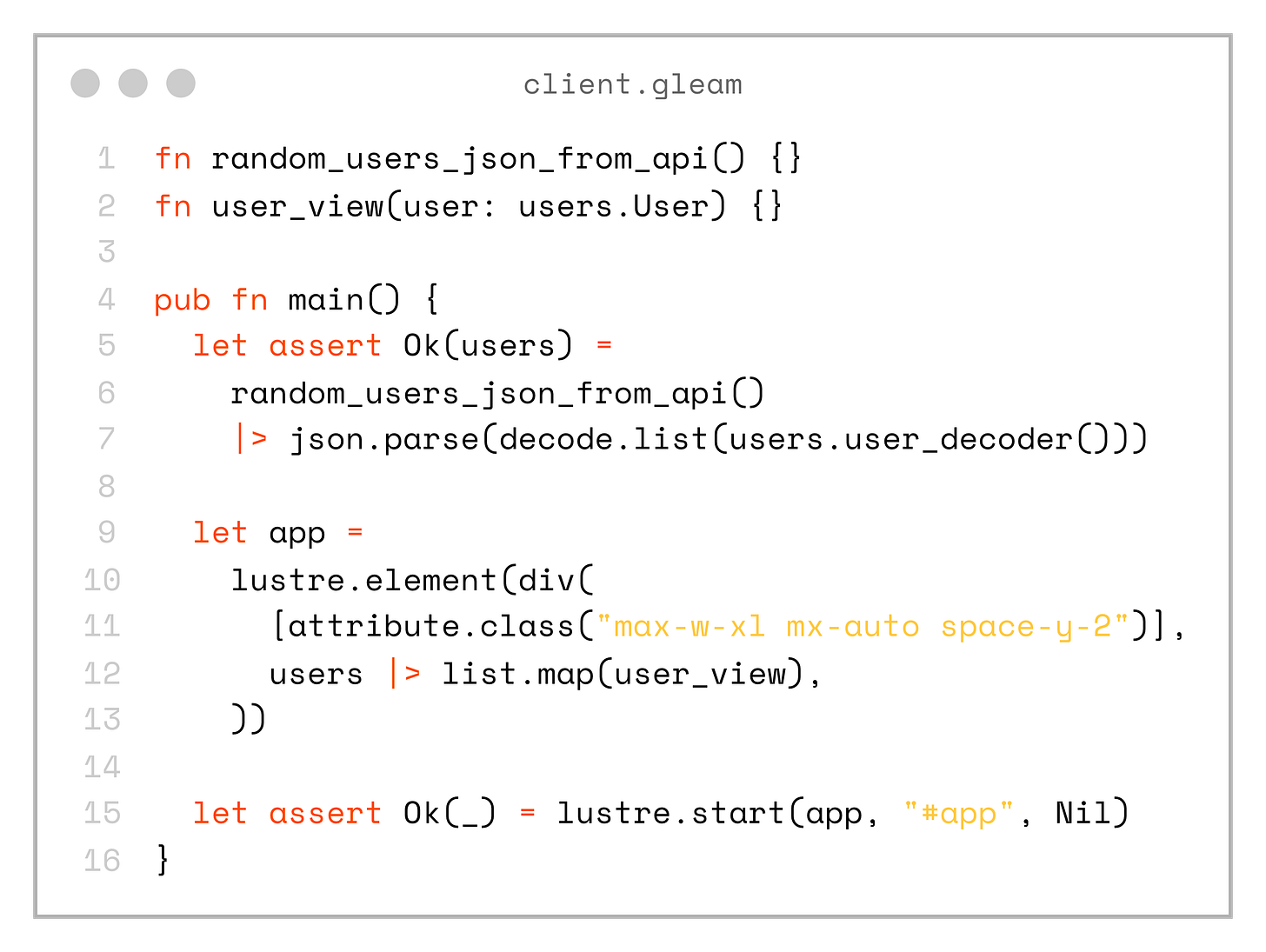

}So, if we put everything together, this is what our complete client app looks like:

fn random_users_json_from_api() {}

fn user_view(user: users.User) {}

pub fn main() {

let assert Ok(users) =

random_users_json_from_api()

|> json.parse(decode.list(users.user_decoder()))

let app =

lustre.element(div(

[attribute.class("max-w-xl mx-auto space-y-2")],

users |> list.map(user_view),

))

let assert Ok(_) = lustre.start(app, "#app", Nil)

}That’s it! We now have type-safety all the way from the database to the frontend, and everything lives in the same repository.

If the database schema changes in an incompatible way and we regenerate sql.gleam, the compiler will immediately show errors in the project that need to be fixed.

The same applies to field renames or similar changes. Since the shared module defines the types, the compiler checks both client and server code, so we avoid unnoticed issues and runtime exceptions.

Plus, the compiler is extremely fast, so running both server and client builds in watch mode gives us instant feedback!

If you want to see a full example, you can check out the project on my GitHub: https://github.com/andfadeev/learn_gleam/tree/master/type_safety